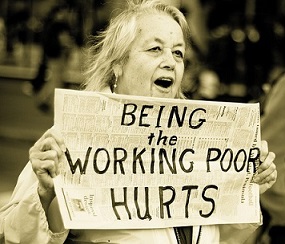

In a nation that has long operated on the principle that an “American Dream” is available to anyone willing to try  hard enough, the term “working poor” may seem to have a bright side. Sure, these individuals struggle financially, but they have jobs — the first and most essential step toward lifting oneself out of poverty, right?

hard enough, the term “working poor” may seem to have a bright side. Sure, these individuals struggle financially, but they have jobs — the first and most essential step toward lifting oneself out of poverty, right?

If only it were that simple.

According to 2012 Census data, more than 7 percent of American workers fellbelow the federal poverty line, making less than $11,170 for a single person and $15,130 for a couple. By some estimates, one in four private-sector jobs in the U.S. pays under $10 an hour. Last month, Senate Republicans blocked a bill that would have raised the federal minimum wage from $7.25 to $10.10 an hour, despite overwhelming public support for the measure.

And these numbers don’t say anything about the many Americans who earn well above the official poverty line and still barely stay afloat. In HuffPost’s “All Work, No Pay” series, the working poor told their own stories, painting a devastating portrait of their day-to-day struggles.

They’re a diverse range of people: single parents, couples with and without children, young women with graduate degrees, business owners, seniors and everyone in between. Their financial situations, however, show many similarities. Jobs generally provide them with the means to barely scrape by, treading paycheck-to-paycheck, earning just enough to keep from going under, swallowing their pride sometimes to take food stamps or visit food banks. Others are entirely out of work, tirelessly seeking employment and relying on other means to survive.

Through their words, we see what it’s really like to be “working poor” in America — and just how much more it looks like rock bottom than most would imagine.

Being working poor means toiling through “pure hell” for next to nothing.

Earlier this year, 55-year-old Glenn Johnson was making about $14,000 a year — or $7.93 an hour — at a Miami-area Burger King. He’d been in and out of the fast food industry for more than 30 years. Recently he watched as his employer reported a 37 percent increase in its quarterly profit, while continuing to resist a minimum wage increase that workers like Johnson have been fighting for.

Johnson described his daily routine as “pure hell.” It’s a nonstop effort to keep the store clean and the customers and his managers — most of whom are less than half his age — happy. “Sometimes, I get home and I’m so tired, I eat dinner, take a shower, lay down to watch TV, and I’m going to sleep,” he said. “Next morning comes. I’m tired, but I’m trying to make it.”

And yet still wishing you could work more.

While Johnson was far from enthusiastic about his work at Burger King, with no computer and few immediate

WASHINGTON, DC – MARCH 28: About 1,500 people seeking employment wait in line to enter a job fair at the Arena Stage at the Mead Center for American Theater March 28, 2014 in Washington, DC. Fifteen organizations and businesses from the Washington Metro area participated in the job fair which was sponsored by Arena Stage and DC Council Member Tommy Wells, who is running for mayor of the district. (Photo by Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images)

prospects of another job, he still wished he could clock more hours. He said he worked about 35 hours a week, but wanted anywhere from 40 to 50, which would make it easier to pay for his $765-a-month rent, gas and any of the things he can’t currently afford. Since Johnson first told his story, his corporate-owned Burger King made him full-time and gave him a raise.

Deangelo Belk, a 21-year-old Wendy’s employee making $7.50 an hour, also knows the pain of not getting enough hours to pay for the things he wants or to help him save enough to move out of his mother’s house. He works around 10 hours a week and said that he’s regularly ignored when he asks for more time.

Because you know you’re lucky to have a job, no matter how awful it is.

Vanessa Powell, 29, works full time in a Goodwill warehouse in Seattle for $9.25 an hour. She holds a bachelor’s degree in English and a master’s in business administration. But with her fiancé out of work, she’s just grateful to have a job, even though she occasionally feels it’s “beneath” her. Even with the job, however, it’s sometimes hard for them to get enough to eat.

“I mean, yeah, it’s dirty work and often demeaning work, but at least it’s work,” she said. “Even though [my fiancé] only worked part time, it was still something. I make enough to cover rent and electric, but we share a cell phone, which is why it’s kind of hard for both of us to search for jobs.”

But finding employment can also risk the crucial aid that helps you get by.

Helen Bechtol, 23, is a mother of two and a community college student with dreams of graduating from the University of North Carolina Wilmington. To help pay for child care, she took a second job, which made her ineligible for day care assistance.

Ashley Schmidtbauer said her family is “not destitute, but we barely make it month to month.” She stays at home to raise her kids and has found there aren’t any easy alternatives. Her husband’s income alone makes the family ineligible for day care assistance. “To be honest, we make roughly $35,000 a year. Somehow, we make over $10,000 more than their limits allow,” she said. “We are the in-betweeners. Not making enough to live ‘comfortably’ — but not ‘poor’ enough to get any assistance either. We don’t expect handouts. We just want what is best for our family.”

Being working poor means knowing it can be expensive just to keep your job.

Joanne Van Vranken, 50, was laid off in 2011. After nearly two years of unemployment, she landed a temporary  administrative assistant position, which requires a 60-mile round-trip commute every day. Van Vranken’s car is in desperate need of repair, but she hasn’t had the money to fix it in years. She’s worried her car will die, which could put her back in dire financial straits. “And I don’t have the money to buy a new one,” she said. “But I have to do it, because we need to pay the bills.”

administrative assistant position, which requires a 60-mile round-trip commute every day. Van Vranken’s car is in desperate need of repair, but she hasn’t had the money to fix it in years. She’s worried her car will die, which could put her back in dire financial straits. “And I don’t have the money to buy a new one,” she said. “But I have to do it, because we need to pay the bills.”

Janet Weatherly, 43, has almost completed her doctoral degree but can’t find employment in her field. Instead, she’s making $11 an hour as a sales associate for a major retailer. Her job is a 45-minute drive from her house, and a significant chunk of her paycheck goes toward gas money. Weatherly’s parents put her car repairs on their credit cards. She’d like to finish her dissertation, but currently can’t afford to get her documents out of a storage unit halfway across the country, much less invest more time in her education.

Or lowering your standards for employment and often still not finding work.

Craig Gieseke is unemployed. At nearly 60, he spent 32 years in journalism, but most of the past decade he was self-employed, so he doesn’t qualify for unemployment benefits. Gieseke doesn’t want assistance. He wants a job, and he’d take pretty much any at this point. Would-be employers tell him that he is “overqualified” — a term he calls a euphemism for “too old” — or that he’d be “bored” doing the required work. “‘Bored’ is hanging around the house all day because you don’t have money to do anything else,” he said.

It means making shortsighted decisions because long-term plans seem doomed.

Linda Tirado knows what it’s like to be desperately poor. She understands firsthand the mentality that leads many people in similar situations to spend money on things like cigarettes and fast food.

“It is not worth it to me to live a bleak life devoid of small pleasures so that one day I can make a single large purchase. I will never have large pleasures to hold on to,” Tirado said. “There’s a certain pull  to live what bits of life you can while there’s money in your pocket, because no matter how responsible you are, you will be broke in three days anyway. When you never have enough money, it ceases to have meaning.”

to live what bits of life you can while there’s money in your pocket, because no matter how responsible you are, you will be broke in three days anyway. When you never have enough money, it ceases to have meaning.”

And living in constant fear of losing what little you do have in an instant.

When Alicia Payton, a 31-year-old mother of two, received a promotion at her job, she thought the increased pay would make the nearly 100-mile round-trip commute worth it. But hope quickly turned to panic when she had a car accident, doing $4,000 worth of damage to her vehicle. Unable to afford immediate repairs or a rental, Payton couldn’t get to work, which she thought would result in her firing.“I’ve worked so hard to get where I’m at, and one simple thing and I’m afraid I’m going to lose everything,” she said. Payton later learned that she had not been fired and had more time to find another way to get to work.

Karen Wall, 38, works as a teacher, cheerleading coach and weekend bartender. Yet money is tight, and all of it goes to keeping her family afloat and paying off her student loan debt. Both of her boys have special needs, so even with the multiple income sources, Wall knows she’s only one disaster away from losing it all. “If I got in a car accident, I’d be homeless,” she said. “If I get laid off from any of my jobs, my kids will end up going hungry.”

Even if things seem manageable now, you could be just a few setbacks away from collapse.

Not so long ago, Kathleen Ann had a house, vacation time, spending money and everything else available to someone with a high-paying corporate job. Then she was discarded in a layoff, cast into a world where she could only find occasional part-time work. Ann now makes less than $20,000 a year, lives in an apartment and has been forced to

Man stresses over his bill while his wife and child stand in the background.

accept that she is poor — a “Used-to-Have,” as she described it.“As a ‘Used-to-Have,’ I know exactly what Corporate America, lobbyists and politicians have taken away from me,” she said.

Being working poor means learning the hard way that investing in your future can actually make things tougher.

Weatherly, who has a bachelor’s degree in English and a master’s degree in public health, is still paying off her six-digit student loan debt. “Things are so bad that I can’t even afford to file for bankruptcy,” she said. “I have applied for hundreds of jobs over the past six years.”

DJ Cook, 36, a teacher who has a master’s degree and lives in a converted garage, described himself as “suffocated by student debt.” “I’ve done everything that I was told to do in order to be successful,” he said. “I’m in a lifetime of debt with no foreseeable answers.”

Carla Shutak thought buying a house with her husband, who was gainfully employed as a civil engineer, would be a wise investment. When he was laid off in 2009, they couldn’t keep up with the mortgage payments and their home was foreclosed on. “My American Dream died,” she said. “Despite doing what we were taught was right by putting 20 percent down and asking for a fixed 30-year mortgage, we were now in our 40s and starting over with nothing.”

And can put you at a disadvantage even as you’re just starting your adult life.

Monica Simon, 24, works full time at an online advertising firm, earning $23,000 a year after taxes. She’s still paying off her student loans and often relies on credit cards to cover basic costs. “Sometimes I get paid and then I have,

maybe, $150 left over for the two weeks,” she said. “I just feel I’m getting way behind where I want to be for my age. I feel I’m just starting my life and I’m already miles and miles behind.”

Even if you saved for retirement, being working poor means using up those funds long before you get there.

Van Vranken spent 16 months unemployed before landing her current temp job. During that time, she used her retirement savings to cover expenses. “I’ve decimated my 401(k),” she said. “Without a permanent job, I don’t know if I’ll be able to rebuild it. I worry I’m going to be one of those senior citizens whose only meal each day is from Meals on Wheels.”

It means facing the harsh reality that while money can’t buy happiness, it’s hard to be happy without any.

Bechtol is consumed with constant anxiety over having enough money to support her two young children. “I go to school and am only paying my parents $250 a month to live in their house and can still barely do it,” she said. “I get so overwhelmed sometimes that I think it affects my parenting, and that’s what I hate the most. I don’t need money to be happy, but I do need money to pay for the resources I need for happiness.”

And realizing that without money, it’s difficult to meet fundamental human needs.

Jason Derr, 37, who earns $10.75 an hour and supports his wife and baby, wishes he and his wife could socialize with the few friends they have. But the lack of money stops them. “We can’t afford to do anything,” he said. “I feel like we are unable to participate in humanity, that being alive has a buy-in cost.”

Similarly, Simon will spend full weekends at home without social interaction. “There will be weekends when I’ll just have to sit home because if there’s a priority between food and going out, it’s going to be food.” Powell added that she hasn’t seen her friends in “six months because I can’t afford to go out with them, and they all want to go out.”

For the working poor, basic medical care is a luxury that’s often sacrificed.

Carol Sarao, 57, a formerly successful musician who now brings in roughly $240 a week writing web content, saves money by avoiding routine medical care and hoping her health remains relatively stable. When she does get sick, she tries to fix the problem herself. “I try to research it on the Internet or I try to find a friend who has antibiotics or something,” she said. “I haven’t had any sort of exam in years. I don’t know how much longer it can go on.”

Sarao described a time she suffered an allergic reaction and desperately needed a hospital visit, but ultimately decided the financial burden wasn’t worth it. “I remember sitting outside of the emergency room and thinking, ‘If I can’t breathe, I’ll go in and get the shot. But if I can breathe, I won’t go in and I’ll save the money,’” she recalled. “I’ve had different cuts that got infected and I just used a hot compress.”

Or a necessity that leads to taking risky chances.

Bernadette Feazell, 65, who makes $8 an hour at a pawn shop in Texas, takes a four-hour bus trip to a dangerous area of Mexico when she has medical needs. She contends the trips save her thousands of dollars. “I need a cavity filled,” she said. “My last Mexican filling fell out, from two years ago. I went down to Nuevo Laredo. It’s very violent.”

Feazell also buys antidepressants across the border. “I buy my Prozac over the line. I speak Spanish,” she said. “Without antidepressants, I don’t think — it would take a toll on me.”

Because not having the money to seek medical treatment doesn’t mean you don’t need medical treatment.

Beverly Hill, 60, was laid off from her full-time job more than six years ago and has been actively seeking employment ever since. She avoids routine check-ups because she can’t afford them. But the last time she visited the doctor, for what she described as excruciating abdominal pain, he found something more worrisome.

“He wasn’t so concerned about my guts as he was about an irregular heartbeat,” she said. “I was hospitalized. Two and a half days in the hospital came to over $40,000. After pleading poverty and asking to be considered a charity case, the hospital relented and lowered my bill to $12,000. I still can’t afford to pay this. I’m eking it out a little at a time.”

“He wasn’t so concerned about my guts as he was about an irregular heartbeat,” she said. “I was hospitalized. Two and a half days in the hospital came to over $40,000. After pleading poverty and asking to be considered a charity case, the hospital relented and lowered my bill to $12,000. I still can’t afford to pay this. I’m eking it out a little at a time.”

Being working poor means coming up with creative solutions in order to eat.

Larry Silveira, 60, who earns $9.25 an hour at his part-time retail job, was raised on a farm and learned how to can vegetables at a young age. He now uses the samestrategies to maximize his family’s limited food supply. “You buy certain vegetables when they’re in season, when they’re cheap. You put them in the freezer and have them in the winter when they’re expensive,” he said. “If you find chicken breast for 99 cents a pound, buy $3 worth and put it in the freezer.”

Derr and his wife keep a “food safety box” in the pantry. “Every time we go grocery shopping, we buy a $1 item — pasta, canned veggies, etc.,” he explained. “At the end of October, we had to live off that box for two weeks.”

And sometimes accepting you’ll just have to go hungry.

Cory Brooks, a senior at George Washington University, works more than full time in addition to her studies and barely makes enough money to eat. “My friends always ask how I stay in such good shape, how I never gained the ‘Freshman 15,’” she said. “I smile and shrug, but what I really want to tell them is that being too poor to buy food is great for keeping the weight off.”

It means sacrificing your own basic needs for those of your children.

Trisha Lovetrove, a wife and mother of two, said that despite her husband’s full-time job, some weeks she can’t afford to buy enough food for the whole family — so she’s the one who suffers. “I feed my children and my spouse, and find an excuse not to be hungry because there’s nothing left,” she said. “Those weeks suck your will to live.”

Kelly Lingo, 22, a stay-at-home mom raising her infant son with her boyfriend, who works full time for $10 an hour, described a similar struggle. “If we do have extra money, it usually goes to diapers or formula,” she said. “Feeding my son, that’s my biggest concern. As much as I don’t like to skip meals, I can do it — I can go without eating if it means feeding my son.”

Or coming to terms with the fact that you may never be able to afford parenthood at all.

At 36, Cook would like to have children someday. But his financial situation makes that seem impossible. “[I]t’s slowly starting to dawn on me that I will most likely never have children, as I would never intentionally bring another child into the world of poverty,” he said. “A house and/or a family is a laughable proposition at this point.”

For the 29-year-old Powell and her fiancé, poverty has also affected discussions about having kids. “My fiancé and I have kicked around the idea of having kids for almost as long as we’ve been together, but we don’t make enough, in all sanity, to allow a child in our care,” she said. “About eight months ago, we just stopped talking about it entirely.”

And if you have children, being working poor means worrying that their lives will ultimately be harder than yours.

Jennifer Blankenship, a 39-year-old mother of four whose family lives on her husband’s $11-an-hour job, has been able to send one daughter to college with the help of financial aid. Still, she, along with a growing number of both middle-classand poorer Americans, takes a bleak view of her children’s future.